The Year That Changed The World

The last two decades of rising inequality and endless crises has finally reached a tipping point.

2020 will surely become one of the most transformative years for global civilization since the end of the Second World War. The Covid-19 pandemic, race protests across the West, the consequences of climate change in Australia, a tidal shift in workplace culture, Brexit... the list goes on.

The events of 2020 thus far are a culmination of the last two decades – like a lobster in a boiling point, the temperature has been ratcheted up through a series of events set in motion by the 9/11 terror attacks. The creation of a new fear and enemies both real and imagined in the Middle East - coupled with the evolution of the modern surveillance state in the name of 'freedom', set us on a course for today.

The collapse of the sub-prime mortgage market and the 2008 financial crash destabilised traditional world orders, and sowed the seeds required for populism in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, culminating most recently in the elections of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson on a wave of support spearheaded by xenophobia, nationalism and isolationism.

It is impossible to understand what we see in the world today without considering the backdrop. The Black Lives Matter protests across the Western world, headquartered in America are - of course - symptomatic of systemic racism dating back centuries. Yet they are amplified by a significant increase in tribalism in both politics and society in the last twenty years. The increasing polarity between right and left, the degradation of political standards - predominantly in flagship democracies like the United States and United Kingdom, the debate between Leave and Remain - all have contributed to a spillover from politics into wider society.

Coronavirus, in a bygone era, would likely have been seen primarily as a medical crisis. There would, of course, have been political scrutiny of any government tasked with dealing with a global pandemic, but let's imagine for a moment that we were facing the same crisis in June 2000.

Bill Clinton is in the final months as President of the United States, and Tony Blair has been in office for just under three years. The world is a very different place. The American psyche has yet to be damaged by the 9/11 attacks, the Iraq War - so utterly devastating to the Middle East but also to trust in the political system - still years away. There are no smartphones, no social media, far less surveillance of everyday life. The world's largest economies are growing, and a general sense of optimism for the future in spite of the growing calls for financial deregulation which would eventually derail the system.

If we were to compare these settings strictly, of course, I have no doubt that the deaths from coronavirus worldwide would have been significantly worse in 2000. Technological advances in medical science have rapidly increased the speed with which we learned about SARS-CoV-2, in a manner which simply would not have been feasible twenty years ago.

Yet for all the mitigations technology has allowed, the challenges we face today are undoubtedly made greater by our failures as a society since the start of the millenium.

Coronavirus entered a world fractured by populism and tribalism. The rampant increase in right-wing nationalism across the world, thrust into power on the wings of a populist message, facing a challenge that rhetoric, slogans and threats cannot solve. The flagrant abandonment of pragmatism in favour of meaningless slogans ("Stay Alert") or outright lies (hydroxychloroquine anyone?) that work in referenda or elections does not stop a virus. At time of writing, the top four countries for coronavirus deaths worldwide (United States, Brazil, Russia, United Kingdom) all have leaders whose power relies either on authoritarian tactics, media control, and populist, nationalist messaging. Trump, Johnson and Bolsinaro all refused to heed the science in the early days of their outbreak, instead opting to seek comfort in some form of mythical, native exceptionalism.

It was a tactic that had been working very well for them - and has, historically, been highly successful in providing electoral success for the right wing. It requires several core ingredients to work: a discontented populace, an imagined enemy and effective messaging. When people feel the world is not working for them, they want it to change, and when facts are off the table, it is always more difficult to make the status quo 'sexy'.

If we take the United States and Britain, we can quickly demonstrate how this is achieved. Both nations had populations rife with discontent, largely driven by growing inequality, the cessation of increasing living standards, and the growing burden of consumer credit. Against the backdrop of death of the American Dream in favour of corporate America, and weariness against the seemingly-endless War on Terror, the Republican Party outstayed its welcome. Barack Obama strolled to electoral success on a message of change and hope. He was able to deliver little of either. Similarly, David Cameron's rebranded Conservative Party ousted a long-standing Labour government - albeit not by a clear enough margin to form a majority, and entered into a moderating coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

The 2008 financial crisis exposed the frailties of two long-standing governments, and replaced them. While economic success was enough to get Barack Obama re-elected, the price of austerity in the United Kingdom left the population divided between the haves and the have-nots. To many more affluent people in Britain, austerity was a necessity to undo the supposed damage of 'last Labour government'. To those affected by it, it was a massive decline in living standards and wellbeing. With no one to turn to, the more radical left-wing vision of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn surged in support, leaving a population angrily divided.

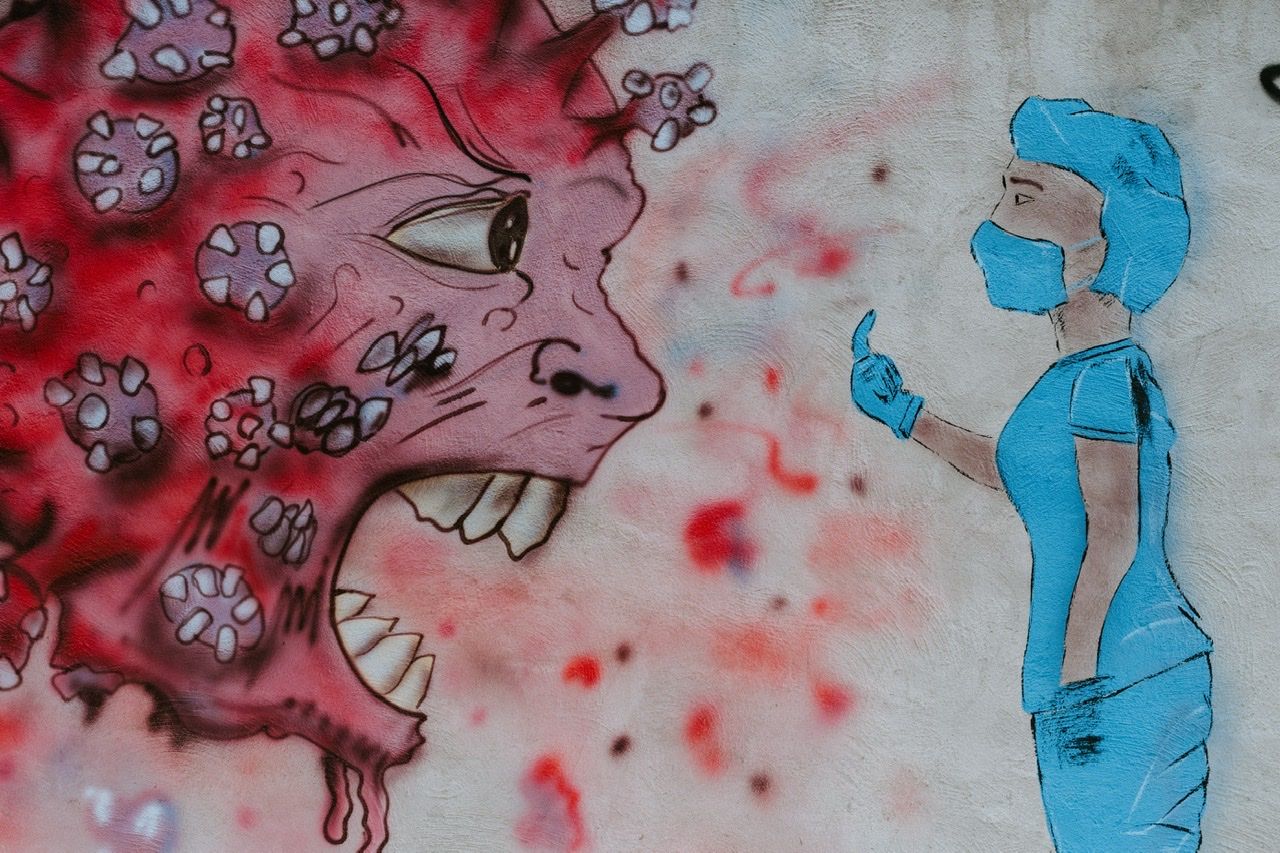

State-side, the election of Donald Trump in 2016 will go down as a political abhorration for the rest of history. Like David Cameron, he did not enjoy enough political support at the polls to receive a compelling mandate, but in the winner-takes-all electoral college, he strode to power with many fewer votes than Hillary Clinton.

His election message was straight out of the populist playbook. He appealed to those Americans who had been let down by the Obama regime; whose industries had not changed with the times and whose workers were left angry and disaffected. He appealed to those frustrated by the liberalisation in society of recent years: the sight of an African-American president still, almost unbelievably, too much for some to stomach.

Trump stoked fears amongst his base and spread lies and disinformation: the reappearance of the Obama birth origin conspiracy, that Hillary Clinton had been involved in a human trafficking and child sex ring. He mocked the disabled, promoted violence against liberals, and promised to – crucially – Make America Great Again. It did not matter if facts were not on his side.

On the other side of the pond, the Cameron administration had been torn apart by the rising tide of euroskepticism. Despite the Liberal Democrats bearing the brunt of voter anger at the polls, MPs such as Peter Bone, Mark Francois, Jacob Rees-Mogg etc. refused to quieten. The looming threat of UKIP, and defections from within his party, led him to take action.

His decision to call a referundum on Britain's membership of the European Union may well go down as Britain's Great Abhorration. The Vote Leave and Leave.EU patriarchs – now entrenched firmly within Boris Johnson's team at Downing Street, edged to victory in the 2016 referendum. As with Trump, misinformation and fear were at the core of their messaging.

They stoked fears of open borders, rising immigration numbers and peddled the same slogans and lies repeatedly to great effect. Many people voted for Brexit on immigration grounds, but many less nationalist sentiments were harnessed and redirected towards the Leave campaign. The idea that Britain would suddenly have more money for the National Health Service, that British fishing industries would be revived, that we would become a hub for international trade. It did not matter – once again – if these were true. It culminated in the slogan "Take Back Control".

Both "Make America Great Again" and "Take Back Control" utilise a sense of nostalgia and entitlement. The say to a voter that they remember the good old days, that they deserve the good old days, and that someone – somewhere – is taking that away from them against their will. Whether you blame Obama, the 'last Labour government', the European Union – it doesn't really matter, given the truth of the accusation is irrelevant, so long as there is someone to blame.

With these components delivered, you can manipulate an electorate to permit exceptional actions. Much as in the early days of Nazi Germany, people are willing to turn the other cheek to actions they find unbecoming of their nation. In Germany, Hitler's rounding up of political opponents and early, violent tactics in silencing rivals were permissible, given that he was restoring Germany's pride in a way the out-of-touch politicians of the Weimar Republic had failed to do. It was coupled with a booming German economy, much like America between 2016 and early 2020 (although if and to what extent that was a bubble, and riding the wave left to him by the Obama administration is a matter for debate).

In America, as happened in the 1930s, many voters have turned the other way at reports (and footage) of ICE detaining migrant children in crude Texan camps along the Mexican border, perhaps comforted by the rationale that Trump was building the wall, restoring American pride that Obama hadn't, and it wouldn't be needed for much longer. Or perhaps the hateful rhetoric that Mexican immigrants were criminals and rapists was all that was needed.

And finally, in Britain, the tolerance of the right wing to the utter incompetence of the British Government's response to coronavirus (and violation of lockdown by its chief advisor). It was all worth it, as if you cut them, they bled Brexit.

2020 is where this tale will likely diverge from the past. We live in different times, in a far more globalised world with knowledge and information at our fingertips. The so-called FAANG platforms (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google) are surely the next to be targetting for censorship, as Trump has threatened (under the guise of preventing censorship, naturally.) Exposure and knowledge of a government's actions and failings is key to it losing support. It is a threat to their existence. Hitler knew this well, and Josef Goebbels - his Propaganda Minister - ensured that the true horrors of the Nazi regime were not widely known, and where possible, wrapped in a cloak of phrases such as "the will of the people" and "the people's government". Likewise the self-glorifying state press in the Kim-dynasty North Korea, or the censored digital world of Xi Jinping's China.

I believe it will be a step too far to blindfold the people of Britain, America and Western Europe – at least long-term. Eventually, the mask starts to slip. In the last month, the Conservative Party have seen a near 30-point lead trimmed to just two points in a recent survey. The British public are angry at the Dominic Cummings Durham fiasco. The rising popularity of Keir Starmer - a comparative moderate in today's political climate - is something of a trend-bucker. Perhaps the British public haven't heard enough from experts, after all.

Tribalism cannot last forever. Human beings and society is nuanced, and attempts to railroad a population down one path must either succeed quickly - usually when faced with some kind of threat - or they disappate. The British public's adherence to their lockdown rules was strong, until the Cummings revelations, and have slipped since. More importantly, the government's authority to enforce them now lies in tatters.

The same will be true of Brexit, and any other attempt to govern on behalf of one base. It will lead to tension, anger, and eventually insurrection through either activisim, electoral change, or insurrection. You cannot leave half of the country behind.

Today, we find this anger starting to rise under the strain of the coronavirus pandemic. The racial tensions simmering and now bubbling over in America come after years of police brutality, overt racism and horrific abuse. Similar - albeit less overt - tensions exist in Britain, as a legacy of colonial slavery. More and more, activism is growing stronger in righting the historic wrongs inflicted on women, ethnic minorities and LGBTQ communities.

Much of the political ideologies of the last 30 years are that of individualism: the so-called light-touch state, the stripping back of the welfare state and the advocacy of meritocracy to justify inequality and protect the gross income disparities in society. The problem for those pushing these ideologies, is that the more you encourage individualism, the more they demand to be seen as an individual and feel empowered to be one. The symbolism of nationality – despite recent efforts by Boris Johnson and Donald Trump – is not sufficient to fulfil one's own identity, or deflect away from the hardships facing someone. Armed with instant messaging, social media, and with almost everyone now walking around with a video camera and means to live broadcast to the entire world, these hardships and frustrations ferment.

We are at a crossroads. We live in interesting times.